Cruising with the snavigator

ArticleCategory: [Choose a category, translators: do not translate

this, see list below for available categories]

SoftwareDevelopment

AuthorImage:[Here we need a little image from you]

TranslationInfo:[Author + translation history. mailto: or

http://homepage]

original in en Gerrit Renker

AboutTheAuthor:[A small biography about the author]

Gerrit didn't like any computers at all until he tried C and

Linux.

Abstract:[Here you write a little summary]

This article presents the snavigator, a powerful code analysis,

cross-referencing and re-engineering tool which is indispensable for

tackling the complexity of maintaining larger pieces of software and

packages in an effective manner.

ArticleIllustration:[One image that will end up at the top of the

article]

![[Illustration]](../../common/images2/article377/a_lot_of_lines.jpg)

ArticleBody:[The main part of the article]

Motivation

An old proverb says that a book should not be judged by its cover. A

similar thing

happens with open source code. However, open source does not equal open

documentation,

and the reading process becomes increasingly difficult the more and

the longer the source files are. I recently had to program

with a piece of software which had half a html page of documentation,

in contrast to over 348,000 lines of Java open source code spread over

more than 2060 files (see figure). In light

of such dimensions, electronic orienteering, reverse engineering and

analysis tools become indispensable, such as the Red Hat source code

navigator presented in this article.

The tool automates many of the tasks one would normally do using

(c)tags, grep, search and replace, but much more accurately and more

conveniently, wrapped in an easy to use graphical interface. See

screenshots below.

Installing under debian

Under debian you can get the whole lot

via the one-liner

apt-get install sourcenav sourcenav-doc

This at the same time takes care of the documentation as

well. The source navigator then resides in /usr/lib/sourcenav/,

you can call the main program via /usr/lib/sourcenav/bin/snavigator

(see tip about symlinks below). Documentation can be found in

/usr/share/doc/sourcenav/html/.

Installation from source

The URL for the homepage of source navigator is http://sourcenav.sourceforge.net/,

actual downloads are from here (sourceforge.net/project/showfiles.php?group_id=51180).

Obtain the latest tarball sourcenav-xx.xx.tar.gz.

While downloading, try to do something else meanwhile - the sources

amount to 55 Megabytes. This does have a positive background,

the whole package is largely self-sufficient. Although it makes wide

use of other libraries such as Tcl/Tk, Tix and Berkeley DB, the correct

versions of these packages are all included. To avoid clashes with

other versions of Tcl/Tk etc on your system, it is a good

idea to

place the installation into a separate directory, e.g. /opt/sourcenav.

The instructions further suggest using a separate build directory,

this works as follows. After unzipping, in the directory which contains

the unpacked sources issue the following commands:

mkdir snbuild; cd snbuild

../sourcenav-*/configure --prefix=/opt/sourcenav

make ## takes a while ...

make install ## might have to become root first

The --prefix option is there to specify the

installation directory. While configure runs, one already gets an idea

about the many languages that snavigator can handle. It is also

possible

to add in further parsers for languages of your choice or making. Once

the installation is finished via make install, the snavigator

is ready

to work and can be invoked as /opt/sourcenav/bin/snavigator.

Instead of extending the PATH shell environment I suggest to use a symlink, e.g. to /usr/local/bin,

instead.

ln -s /opt/sourcenav/bin/snavigator /usr/local/bin

The main executable is a shell script which needs to know its

directory.

Thus it gets confused if called via a symlink. This can be remedied

by changing the following lines in /opt/sourcenav/bin/snavigator;

instead of

snbindir=`dirname $0

use

prog=`readlink -f $0`

snbindir=`dirname $prog`

The -f option to readlink(1) creates a canonical

pathname representation, this means it even works if the file is

accessed via a very

long chain of nested symlinks.

Using snavigator

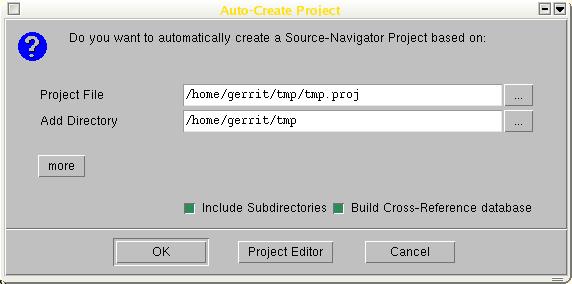

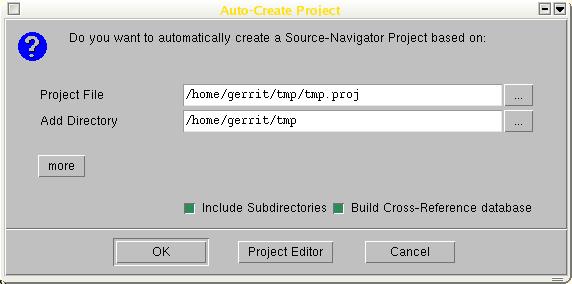

The first time snavigator is invoked, it asks for directories

containing

source files, as the following screenshot shows. Languages which are supported include, but are not limited

to, Java, C, C++, Tcl, Fortran, COBOL, and assembly programs. Once

given the details of source code locations, it independently builds

a project database which includes referencing information, class

hierarchies,

file inter-dependencies ... and much more. Depending on the size of

your

project, it takes a short while to build. Once done, the database

can be queried and additional information be asked about the code.

The following just highlights some of the features, to give you an

idea. An illustrated user guide, as well as a

reference manual, is included in the html directory of the

installation.

Languages which are supported include, but are not limited

to, Java, C, C++, Tcl, Fortran, COBOL, and assembly programs. Once

given the details of source code locations, it independently builds

a project database which includes referencing information, class

hierarchies,

file inter-dependencies ... and much more. Depending on the size of

your

project, it takes a short while to build. Once done, the database

can be queried and additional information be asked about the code.

The following just highlights some of the features, to give you an

idea. An illustrated user guide, as well as a

reference manual, is included in the html directory of the

installation.

Project management

Part of the suite is an editor

with syntax highlighting, this can

also be used for pretty-printing files. The following screenshot

depicts the main editor window. It is almost like a development

environment, comes with such things as a debugging facility, project

build commands, version control and the like.

In particular, the big green arrows on the menu work just as in a

web browser. The project editor allows one to control the database

information, e.g.

if a file has just been updated; to add or delete files from the list

and other management tasks. All files are treated as one

big project. So if changes are committed to, you can update the

database information

via Refresh Project or Reparse Project.

When in the editor window, highlight something, e.g. the name of a

function such that the highlighted region appears in yellow. Then

right-click with the mouse - there is a choice to find either (a)

the declaration of what you just have highlighted (e.g. a

header file)

or (b) the implementation of the highlighted symbol (e.g. a .cpp

file), plus a few more useful options.

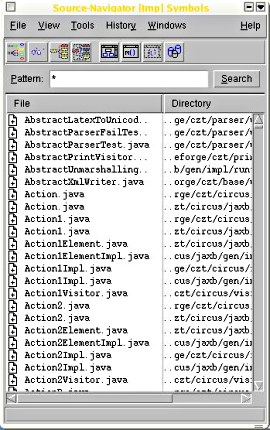

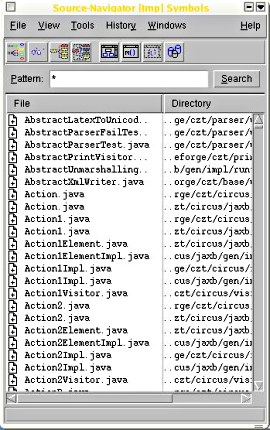

Symbol browser

This is the first window that opens up after populating the

project database. Usually it contains filenames, but it can also display class

methods, function symbols and the like. When a

filename is clicked upon, the editor will be opened with that file.

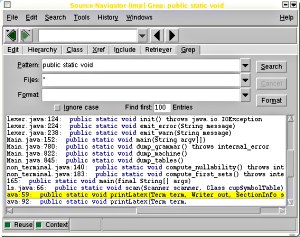

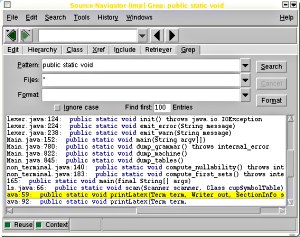

The grep window

This does what the name says, it provides a

convenient gui for grepping

through all involved source code files. Matching entries are

highlighted

and hyper-linked, the source code can thus be browsed as if it were

a bunch of web pages. As the screenshot shows, the respective file

and location can be selected and by simply clicking that entry you have

the editor opened at the right position. (This particular search term

gives positive results in many Java files :)

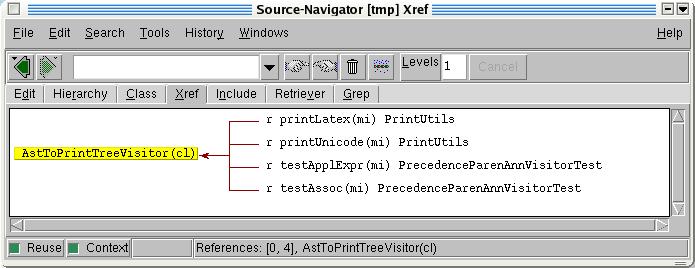

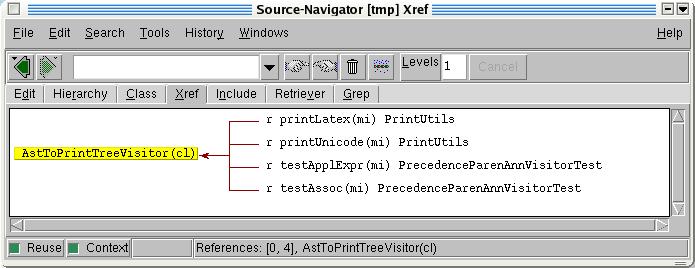

Xref window

Here we have a cross-reference list of all the symbols, in particular

one can see which methods read (r), write (w), ... on which data and

see

the relationships among symbols, depicted in a hierarchical manner. The

entries are clickable.

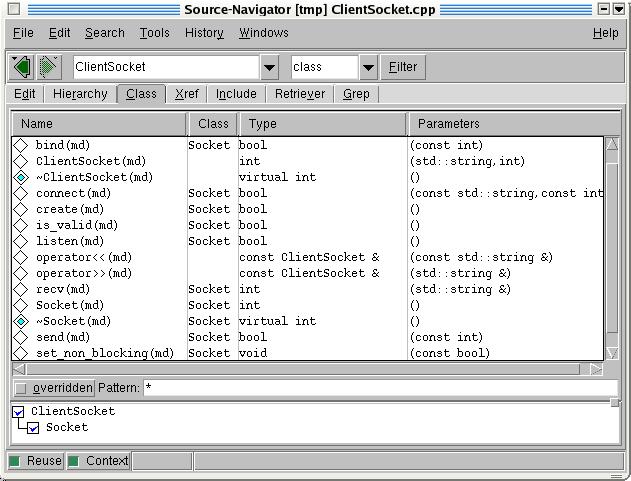

Class window

This interface aggregates all useful information one

wishes to know about classes in an object-oriented language. In

particular, super- and subclasses are shown, as well as attribute and

method names along with their parameters. For a change, the window

below shows a C++ ClientSocket class which inherits from Socket

and has quite a few methods. Again, by clicking any of the entries you

can open an editor window at the appropriate position.

Other alternatives

cscope is an interactive, console-screen based C source

code browser (it can do C++, too). It has some of the

functionality

of snavigator, a screenshot is here.

In fact, it is much older and has been used in many

and very big projects. Its homepage is http://cscope.sourceforge.net/.

But you need not even go there - it is built into vim and can

be

used in much the way (g)vim is used in combination with tags.

Simply type in

:help cscope

in your vim session to check the available options. There

are a few derivatives of cscope. Freescope

is a cscope clone which has some added functionality

such as symbol completion. There is now also a KDE GUI frontend to

cscope called kscope, it can be found on http://kscope.sourceforge.net/.

Conclusions

For anyone involved in at least partly re-engineering or integrating source code, snavigator is a very useful and powerful tool. I once had an older Qt application which unfortunately did not work with the current version of the Qt library. By looking at the error messages and cruising a little with the snavigator, I had soon found out that only the parameter list of one function needed to be changed. Using the click-and-locate functionality, it was possible to bring the entire software package up to date in just a few minutes.

![[Illustration]](../../common/images2/article377/a_lot_of_lines.jpg)

Languages which are supported include, but are not limited

to, Java, C, C++, Tcl, Fortran, COBOL, and assembly programs. Once

given the details of source code locations, it independently builds

a project database which includes referencing information, class

hierarchies,

file inter-dependencies ... and much more. Depending on the size of

your

project, it takes a short while to build. Once done, the database

can be queried and additional information be asked about the code.

The following just highlights some of the features, to give you an

idea. An illustrated user guide, as well as a

reference manual, is included in the html directory of the

installation.

Languages which are supported include, but are not limited

to, Java, C, C++, Tcl, Fortran, COBOL, and assembly programs. Once

given the details of source code locations, it independently builds

a project database which includes referencing information, class

hierarchies,

file inter-dependencies ... and much more. Depending on the size of

your

project, it takes a short while to build. Once done, the database

can be queried and additional information be asked about the code.

The following just highlights some of the features, to give you an

idea. An illustrated user guide, as well as a

reference manual, is included in the html directory of the

installation.